Oil prices dropped off a cliff Monday as a key futures contract went “negative” for the first time in recorded market history. Then, the selling continued Tuesday.

Oil will probably have rebounded by the time you read this which is great for savvy investors.

Today we’re going to talk about what really happened, what that means for you money, and, of course, how to trade that information based on what happens next.

Hopefully, for some terrific profits!

First, what are “negative” oil prices?

Oil is traded using a series of futures contracts that correspond to specific monthly deliverables. Prices typically vary by month as a function of anticipated demand, spot prices, and the remaining time until delivery.

As I prepared this column for example, the May 2020 Globex CME contract is trading at $5.38, while the June 2020 contract is $13.63, and the July 2020 contract is $22.12.

Figure 1 CMEgroup.com

Figure 1 CMEgroup.com

This makes oil very different from stocks where there is no underlying commodity and no delivery obligation, and prices are quoted based on a limited number of shares at any given moment in time.

Oil prices normally converge as buyers – think airlines, refineries, transports here – get closer to actually taking delivery of the oil they’ll need. That’s why most oil prices are most typically quoted using the nearest term contract.

Monday, however, a very different situation emerged.

Prices on the May contract tanked – sorry, couldn’t resist the pun – because “nobody” wanted more oil in May and storage facilities were full. The situation got so bad before the end of trading that prices actually settled at negative $37.63 per barrel.

Normally prices are positive because that’s what buyers have to fork over per barrel to take delivery but in this instance, they became negative, effectively suggesting that producers would have to pay buyers to take their oil.

To put this in context, imagine taking your favorite car out for a drive.

Normally, you’d pay to fill up because you need the gasoline and the station has effectively “stored” it for you until you needed it. Had you gone driving Monday afternoon, the station owner would have paid you to take the fuel!

This is a “180” that has never happened before with oil futures contracts.

Second, why did prices drop so fast?

This is where things get interesting and, frankly, problematic.

The exchange traded funds that everybody thinks are so neat are, in fact, huge problems in situations like this one, especially when commodities are involved.

Take United States Oil Fund LP (NYSEARCA:USO), for instance.

The financial alchemists who created USO never intended to take delivery of the West Texas Intermediate Light Sweet Crude oil prices it tracked. By design, that responsibility falls to the USO’s administrator and general partner – the Bank of New York Mellon and U.S. Commodity Funds, LLC respectively.

This created a double-whammy:

- Neither the bank nor the fund operator were any more prepared to take delivery than you and I; and,

- Storage facilities in and around Cushing, OK – the primary delivery and price settlement point for WTI crude – were full so there’s no place to put more oil.

Normally demand would make this impossible, but the coronavirus has effectively eliminated that which, in turn, forced prices down at every step in the demand curve.

This makes sense when you think about it.

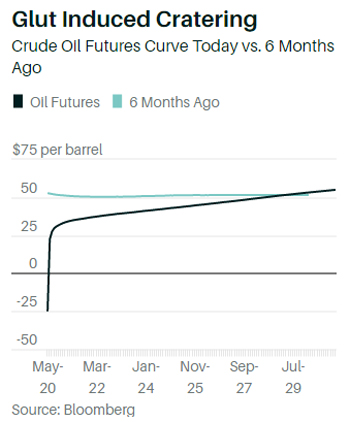

Six months ago, demand was constant pre-coronavirus, and you could see that clearly in the oil futures curve (which reflects prices by month over time). Then, demand vanished as social distancing came into effect.

People aren’t driving as much, if at all and the drop in related fuel consumption is so graphic that many auto insurers are giving rebates or handing back premium to compensate consumers who have parked their vehicles. There is so little gasoline needed, that there are now reportedly 13 states where the average cost of a gallon of gas is less than $1 if memory serves.

At the same time, air travel bookings are down 103% year-over-year with the average domestic flight now carrying just 10 people per hop. International flights reportedly average just 24 people per flight and that’s, mind you, with something on the order of 90% of capacity already removed from the system.

Trains, factories, trucking fleets… you name it … demand simply fell off a cliff.

The June crude contract is now under pressure as traders come to terms with the fact that May may be just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Again, as I prepare this article ahead of publication.

Many people are banking on a recovery, but I think the demand fallout will persist through much of the summer. In fact, I think that oil demand may be another 45 million barrels per day lower than it would under normal circumstances versus “just” the 39 million barrels I’m hearing bandied about in the press.

As a result, I think there’s a good chance the June contract may go “negative” too because the trajectory is similar if the company doesn’t jumpstart demand and reopen soon.

Which brings me to the fun stuff… how you trade a situation like this one.

Normally, I’d suggest USO itself because I think oil will come roaring back when demand resumes. It’s dropped 79.48% since January 6, 2020, and is trading at just $2.70 as a write.

However, I’m suspect about USO itself. Many investors think it’s a proxy for oil but that’s not true. In fact, USO is another in a long line of commonly misunderstood trading products that has no place in an average retail investor’s portfolio.

I think there’s a good chance USO will be repriced or even liquidated if the prices for crude don’t come back in line relatively quickly. Some of that is going to be simply a repricing as more futures contracts “roll” – which is a technical story for another time.

The situation reminds me another fancy-pants ETN that blew up in early 2018, XIV.

Like USO which is intended to track a derivatives pricing model based on oil, XIV was supposed to capitalize on the gradual erosion of volatility that existed at the time. However, XIV imploded and became worthless almost overnight on Monday, February 5th, 2018 when the Dow Jones got pummeled and volatility exploded.

Anybody banking on a decline in volatility got scorched.

I recall vividly talking to several traders that evening as XIV dropped 90% in after-hours trading. Like oil traders this week, they lost billions. XIV, incidentally, did not reprice like I expect USO to and ceased trading February 20th.

Speaking of which, I think USO could have lottery ticket potential if the Bank of New York Mellon doesn’t pull the ETF. My suggestion would be to purchase long-dated call options like the 15 January 21 $6 Calls, instead. They’re trading at $0.36 to $0.37 cents as I type but are likely to drop further while USO gets its act together which means you could get even a better bargain with more upside potential.

Or, if that’s a bit to “hot” to handle or you don’t have the trading chops, consider buying a major oil player like Schlumberger Ltd. (NYSE:SLB).

I’m drawn to the fact that the company as significant number of long-term contracts that can carry it through the next 12 to 24 months without undue price exposure.

What’s more, Schlumberger recently announced a dividend cut so it’s beaten down at just $14.69 a share, roughly half of where it was trading at we entered 2020. LEAPS calls would be a great alternative here, too.

In closing, these are both highly speculative trade suggestions so treat them accordingly.

Until next time,

Keith

The post Why Oil Prices Really Crashed Monday (and What to Trade as a Result) appeared first on Total Wealth.

Powered by WPeMatico